- Home

- Shani Mootoo

Valmiki's Daughter

Valmiki's Daughter Read online

Valmiki’s Daughter

Shani Mootoo

Copyright © 2008 Shani Mootoo

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Distribution of this electronic edition via the Internet or any other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal. Please do not participate in electronic piracy of copyrighted material; purchase only authorized electronic editions. We appreciate your support of the author’s rights.

This edition published in 2010 by

House of Anansi Press Inc.

110 Spadina Avenue, Suite 801

Toronto, ON, M5V 2K4

Tel. 416-363-4343

Fax 416-363-1017

www.anansi.ca

LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA CATALOGUING IN PUBLICATION

Mootoo, Shani, 1957–

Valmiki’s daughter / Shani Mootoo.

eISBN: 978-0-88784-898-8

I. Title.

PS8572.O622V35 2008 C813’.54 C2008-902023-5

Cover design: Ingrid Paulson

We acknowledge for their financial support of our publishing program the Canada Council for the Arts, the Ontario Arts Council, and the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund.

For SJD

Prologue

24 Seconds

SHE IS SEATED ON THE BED IN A SEA OF BRILLIANTLY WRAPPED PRESENTS.

He watches her, grinning, and he makes silly comments as if he fully agrees with all that is happening. The grinning hurts, but if he doesn’t grin he will cry. He’d rather switch off the light in the room, throw a net over her, wrap her tightly in his grip, and flee with her. Take her deep into one of the forests hunting with him. Just the two of them. Never to return. Instead he stands still, jokes about the presents. What he wishes he would or could do and what he actually does are related only by being perfect opposites.

Once, she doted on him. Then, suddenly it seems, she sees right through him. He is sure of it.

Suddenly. Everything has happened so suddenly.

His wife certainly saw through him long ago. But he credits Devika with a vision larger than that of his daughter. Devika’s vision encompassed her own long-term welfare as well as that of his two girls, their girls — young women, rather. Devika’s vision, too, held dear nothing but respect, the utmost, for how things are expected to be. He and Devika have these values, if nothing else, in common.

Of course, it isn’t really so “suddenly” that his daughter reared up and threatened to undo them all. What is sudden is him seeing her for who she is, as if for the first time. Even so, he has done not a damn thing to help her, he taunts himself, and now she is on the verge of leaving. He knows this is good for them all, or at least for those who will remain behind. He has no idea if it will be good for his daughter. If only he could take her away. Tell her his own story so that she might create a different one.

He can only hope. Such a frail thing, hope.

He needs, for his own sanity, to point to the moment, to the specific sliver of time when his eyes began, finally, to open, when he might have done something — or everything — differently. The point on which he might hang regret.

Regret is so much more palpable than hope.

Was it just that day, that rainy September day — a year ago now — that had begun with his daughter barging, even before he had fully awakened, into his and Devika’s bedroom, insisting on having her own way? He should have stood up, not to her, but to his wife. He should have let his daughter do all that she wanted, be all that she was. But in a place like San Fernando, that was impossible.

I San Fernando

24 Hours

Your Journey, Part One

IF YOU STAND ON ONE OF THE TRIANGULAR TRAFFIC ISLANDS AT THE top of Chancery Lane just in front of the San Fernando General Hospital (where the southern arm of the lane becomes Broadway Avenue, and Harris Promenade, with its official and public buildings, and commemorative statues, shoots eastward), you would get the best, most all-encompassing views of the town. You would see that narrower secondary streets emanate from the central hub. Not one is ever straight for long. They angle, curve this way then that, dip or rise, and off them shoot a maze of smaller side streets.

There is, at that Chancery Lane intersection, a flow of traffic around the white-painted triangular concrete islands that involves some nudging, constant car-horn blaring, frantic bicycle-bell ringing, face-reddening expletives, and curses of one’s forefathers and progeny. Streams of cars jerk forward, halt too suddenly, and then as if by magic, flow forward effortlessly, traffic lights and wardens momentarily rendered unnecessary.

Imagine you are a tourist let down from the sky, blindfolded, in the middle of a weekday, onto one of those traffic islands. Your senses would be bombarded at once. You would descend into a cacophony of sound, and a cacophony, yes, of smell. Car horns would hoot and toot in varying lengths and tones, sounding, with a little imagination, like a modernist noise symphony that would include outbursts of the nut seller’s arcing melody, “Nuuuuhts, nuts, nuts, nuts, nuuuuhts, fiiiif-ty cents a baaahg.” You’d hear theatrical steupses, and people hawking unabashedly, dredging the recesses of their craniums before spitting — should you open your eyes prematurely — amphibian-like yellowish or greenish globs hard onto the sidewalk. You might be lucky enough, if you arrive at the right time of the day, to hear rounds of clarion bells on a descending partial scale. The church’s organ would no sooner soar upward than the choir would be heard in practice: short bursts of a phrase repeated, repeated, repeated until it is mastered, then longer sections practised until the entire hymn is finally belted upward ever more. Outside the church, people would be hurling greetings at one another. Some would be hailing taxis, and at least once a day there is bound to be the theatre of a spurned lovers’ quarrel, all the better when not two but three are involved. The taxi drivers at the several stands in the area, and the nut sellers perched like ground-bound gargoyles at every intersection, could probably intervene as witnesses or judges, for from their positions they might well have seen the affair unfold from beginning to end. But in the interest of business as well as their own longevity they stay out of the fracas, which sometimes involves knives or cutlasses that make the proximity of the emergency ward useful. From many sources you will hear radio commentary on a cricket match. Sailing in on a breeze from one of the side streets, the faint music of a steel-pan orchestra might also be discerned. Human-like cries overhead might startle you at first, but you would soon easily distinguish the sounds of greedy competitive seagulls from those of agony and despair emanating night and day from the various wards at the hospital.

Despite the aural melee, what might well overwhelm you are this intersection’s odours. Before you remove the blindfold and see the blue haze caused by the exhaust fumes of cars, scooters, and trucks, your nostrils will have stung from it, and your skin will have tingled and turned greasy. The aroma of roasting peanuts, of corn boiling in garlic-infused water, of over-used vegetable oils in which split-pea fritters with cumin seeds have been fried, of the cheery, spicy foreignness of the apples and grapes being sold in the open-air counter on the corner, would activate your taste-buds, and in spite of the surrounding unpleasantness, even if you had eaten not long ago your stomach would argue that it was ready and able again. A person might pass near enough for you to be assailed by his or her too-long unwashed body. And you might well be assaulted by the equally offensive fragrance of another passerby’s underarm deodorant, which, having been called upon to do its duty, swelled uncontrollably in the heat

. The stink of urine would, of course, be there, and surprisingly, that of human excrement, rising high on crests of wind and then thankfully subsiding. And sailing in, all the way up to this high point, on a breeze from the Gulf not too far away, would be the odours of oil-coated seaweed, dried-out barnacles that cover fishing vessels beached at the wharf below, and scents from foreign ports. If this olfactory mélange were audible, it would indeed be cacophonous, made more so by the terrible nostril-piercing stench of incinerated medical wastes and bed linens, intermittent effluxes from two tall chimney stacks set at the rear of the hospital. Your stomach, opened up moments before in greedy receptivity, might feel as if it had been tricked and dealt a dirty blow. Then again, it might be the season when the long, dangling pods of the samaan tree (the unofficial tree of the city, planted and self-sprouted everywhere), which resemble a caricature-witch’s misshapen fingers, split — and the entire town is drenched in an odour akin to that of a thousand pairs of off-shore oil workers’ unwashed socks, an odour as bad as, but more widely distributed than, the effluvia from the medical waste incinerator.

The air temperature would be high, as befits an equatorial midday. If you remained standing on that exposed traffic island too long, your skin would redden and become prickly in no time, as if it had been rubbed with bird-pepper paste.

SO, TAKE THE BLINDFOLD OFF. OPEN AN UMBRELLA AGAINST THE SUN and have a look around. But where to begin your visual introduction? The long view in any direction seems better than the one before, especially if you ignore the closest — that of a row of beggars sitting on their haunches on the sidewalk, with arms outstretched, reaching for, but not touching, the clothing of the passersby. Those beggars attempt to hook pedestrians’ eyes with their own, muttering their plaintive invocations: “God bless, God bless.”

You might or might not have noticed, depending on where you have dropped from, that the people on the streets are mostly of Indian and of African origin. Indian or black. You’d likely notice that most of the beggars are Indian. But you might not.

You will realize that some of the teeth-sucking you’ve been hearing came from pedestrians on the hospital side of the intersection forced to cross over the sleeping body of a homeless man, or having come upon the pee-sodden body of a young and out-cold drunk woman.

Well, perhaps it’s not all that difficult to know where to begin your introduction. If you can lift your head up, away from the beggars, the homeless, and the drunk on the sidewalks and take in the six-storey buildings of the General Hospital, you will see that they form an imposing and eerily beautiful backdrop to one side. Painted stark colonial white, the hospital rises higher than any other building in view, yet each section is capped with the traditional V-shaped roof of a simple family house, a shape meant to quell its simultaneous grandeur and foreboding.

Outlining the edges of the hospital property is a low white concrete fence topped with tall silver-painted iron spurs, V-ed like the blades of an overly long sword. There is a formal entrance, with a sentry’s concrete hut dividing entry and exit lanes. The sentry box is often empty, and cars and pedestrians usually come and go at will. But the sentry is there today. He is outside of the box, dressed in his uniform of starched and pressed khakis, with a khaki cap pulled low on his forehead. He leans — only his shoulders touch — against the side of the box, his sole focus the young woman in front of him, with whom he chats through pursed lips. Only she can hear what he utters. One of his legs is raised back, its foot bracing against the wall. His arms are folded high on his chest. If his eyes were fingers the young woman before him would be at his knees. Cars still come and go at will.

At this entrance, also, is a group of men huddled over a radio. It is from here you heard the cricket commentary, and the men who listen seem, from their clothing and demeanour, to have nothing in common but their interest in cricket.

Because you can still hear it, you look around trying to spot where the sound of the steel-pan band comes from. The music seems to come from one side of the town one minute and then, whipped away on a breeze, from another direction. You try to hold on to the mellifluous sounds, but they float in and out quickly. Behind the entry and fencing, well-tended lawns spread out and surround the hospital, and lush islands of Calla lily — reds, yellows, purples — direct the flow of pedestrian traffic. The driveway that cuts through the hospital grounds is bordered by a single row of palm trees whose trunks, from the ground to a height of about six feet, are washed in the same white paint as the fence and the buildings, a holdover from colonial days when paint was thought to deter destructive bugs. Some concrete benches in a semicircle, painted that white again, are set on the lawns under the spreading shade of flamboyant trees whose trunks were not spared the whitening either. The benches were originally meant for use by patients and their visitors, but serve more often, day and night, as beds for the homeless and the uncared-for insane. Across each and every one lies a spectre of a figure, a body bound in rags that reek, knees pulled up to chest, one arm pillowing the head against unyielding concrete.

The regulars at the hospital, in addition to some long-term-care patients who won’t be going anywhere in a hurry, or ever, include nurses, and Drs. Peters, Rajkumar, Krishnu (who also has a private practice in the town centre), Tsang, Chu, and Mahabir. Turn around now and face the north. Your perch, after a spread of some ten yards or so, drops down a steep road, Chancery Lane. The slope is like the long handle of a ladle. To one side at the bottom, the ladle’s bowl, is the hospital’s and shopping district’s principal parking lot. On the other side is a descending row of colonial-style buildings, the offices of lawyers and notary publics. The commercial main street begins at the base. There, just before the main street turns and disappears, you can see a gas station, its red-and-white Texaco sign spinning, The Chase Manhattan Bank, Khan’s Clothing and Household, Bisessar’s Furniture and Rug Emporium, and part of Samuel’s Sporting Goods Store. Then the street curves away and disappears around a bend. If you were to continue around that bend you would find a supermarket, a building of doctors’ private offices — Dr. Krishnu has his there, and a hairdressing salon is on another floor — Maraj and Son’s Jewellers, and the city’s only bookstore.

Raise your eyes; keep looking out into the distance to where the yellow and silver waters of the Gulf of Paria are studded with red-and-black oil tankers awaiting their turn at the refinery’s docks. Between that high horizon and the town at the bottom, you see a sea of green — the fronds of palm and coconut trees mixed with sampan, flamboyant, Pride of Barbados, mango trees — dotted with a confetti of colourful roofs — reds, greens, silvers, blues. These mark the residential neighbourhood of Luminada Heights. It is here you find the residences of the city’s more prosperous citizens, including Dr. Krishnu — who, with his wife and their two children, lives in an architect-designed house — and the Prakashs. When the Prakashs bought land here several years ago — their son, Nayan, had just become a teenager — they built a mansion Ram Prakash had sketched out on a foolscap sheet one sleepless night: four bedrooms for his family of three, and three baths. The Morettis (not rich, but white) still own a house in Luminada Heights even though they long ago returned to wherever it was they sprang from in search of paradise and independence. Their house, just up the way from the Krishnus, is leased now to an off-shore drilling company, and in it lives a single American man who makes good money working in the Gulf on one of the rigs he can see from the patio of the house.

Look behind you, to the south, down Broadway Avenue. The avenue is wide, divided by a high island of tended grass, down which runs an uninterrupted row of Pride of Barbados trees. On the left and the right sides you will see two-storey concrete houses, all set behind concrete walls whose paint has long washed, or been peeled, away. The shoemaker, some of the hospital’s nurses and workers, clerks in the law courts nearby, some taxi drivers, teachers, servants, an ironer, the piano teacher who has her “school” in the living room of the top floor of the house she rents, an

ageless man who lives by himself and wears dresses (he had ambitions to be a fashion designer and dressmaker but was unable to find clients and sews only for himself now), and a midwife are among those who live on Broadway. As that avenue curves off and disappears, taking with it an old, once-prosperous neighbourhood, your eyes are naturally carried eastward toward a narrow band of more private houses and more trees. The lushness and the randomness of vegetation suggest that much has sprung up of its own accord, without discouragement. Behind and between are snippets of yet more houses, but you are unable to see clearly the shape and nature of all that lies there, so you gravitate right back to the busyness of your intersection. All around you, cars, mostly simple compacts, some held together, it seems, by duct tape, slide around the islands, near accidents only just avoided by the long, hard, loud engagement of horns.

Unexplored as yet is Harris Promenade. You have to step off the island and make your way very, very quickly, across the street, making sure to catch the eyes of the drivers as you do so. The sun, however, almost directly overhead, reflects and glints wickedly off the cars’ windshields. If the tinted windshields and windows — purple is the fashion here — ward off glare and heat for those inside the cars, they make it doubly difficult for a pedestrian to see if she or he has caught the eyes of the drivers. So take extra care in crossing.

Even as you cross, you will notice off to your right, which is also to the right of the promenade, several policemen, and you will wonder why none directs traffic. The police mill about the mouth of the police station, which yawns wider as you approach the promenade proper. Groups of them seem to be waiting for something, anything, to happen, and so to be called for an assignment, but they do not act unless ordered by their superiors.

Cereus Blooms at Night

Cereus Blooms at Night Polar Vortex

Polar Vortex He Drown She in the Sea

He Drown She in the Sea Valmiki's Daughter

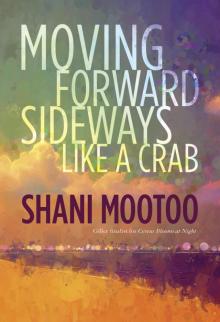

Valmiki's Daughter Moving Forward Sideways Like a Crab

Moving Forward Sideways Like a Crab